My Father Xue Mo and I (5)

By Chen Yixin

translated by J. C. Cleary etc.

Part Five

People always say that special people must have a different look. Whether or not my father is a “special person,” I would not presume to say. No matter where he goes, there are always people who say that with his bushy eyebrows and deep-set eyes, my father looks very much like a foreigner. As for my father’s appearance, I am very puzzled: our ancestors all looked very ordinary, and our blood relatives now are all very normal. He is the only one who is “a fierce fellow with leopard's head and round eyes, a Black Leak God with tiger's beard and steel whiskers.”

People who have met my father are almost all struck by his appearance, especially his beard and the cinnabar-colored mole between his eyebrows. Someone once said: “When you look at his beard, Xue Mo looks like a demon king. When you look at the mole between his eyebrows, he also looks like a Buddha.” When my father heard this, he laughed out loud and said: “Xue Mo is neither a demon nor a Buddha. He is just a crazy old guy.”

But the reason our whole family believes in Buddhism is definitely not because of the cinnabar-colored mole on father’s forehead.

According to my grandmother’s account, when my father was little, he believed in Buddhism, but he was not one of those people who always have “Amitabha Buddha” on their lips. Only later, when I was organizing my father’s diaries, did I come to know that when he was seventeen he had already paid homage to Master Wu Naidan of Song Tao Temple as his teacher. When I was little, he often told me Buddhist stories. He told me that I shall not step on ants and bugs, that I must not deceive people, that I shall help people, that be a good person in the future.

In our native village there was a Vajrayogini cave. My father said that this was a famous place, but was unknown to the people of Liangzhou. When I was little, our family often went there. At that time, that mystic cave had not yet been sealed off, and it was very dim and dark inside. In the cave there were many passageways of different sizes, twisting and turning and uneven, going up and down and right and left. Every time we went there, our family would spend a long time with old man Qiao, who watched over the cave. My father would rub the minerals on the walls of the cave sparkling like crystal and say: “This is a great being!” Associated with the Vajrayogini cave, there was also the story of Zhang the butcher and five girls. This story was passed along by oral tradition, and communicated from the Western Xia kingdom [which ruled in this region 1038-1227 C.E.] up till today. A veil has already been cast over the Tangut people [who founded the Xixia kingdom], and they have disappeared into the mists of history. But the Vajrayogini cave, along with this story, still tells the tale of those special causal conditions. Later, this went into my father’s novel Curse of Xixia.

When I was seven, under my father’s guidance, I began to cultivate Buddhist practice in a imitating way. Every day I would make full prostrations and recite the Hundred Word Mantra. Before dawn, at 5 a.m. when the world is all quiet, I would silently recite the holy sounds that have been handed down for a thousand years, and peacefully listen to the obscure, hard-to-understand texts of the sutras. I do not know whether doing this increased my wisdom, but it truly softened my heart. I began to hate the way I had removed the wings from bees before. I began to stop my companions from shooting things at birds. I began to put my spare change in the bowls of beggars…. Later, I slowly came to understand that it was during this period that I learned respect and a sense of gratitude. Although at that time, I had still not memorized any scriptural texts, and I had not recognize the special characteristics of the different Buddha images, nevertheless, it was enough to have influenced my life.

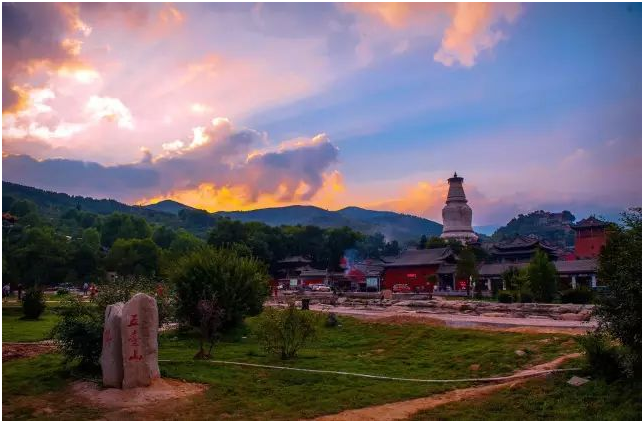

Not long after this, our family went on a pilgrimage to Wutai Mountain. This was a pilgrimage in the true sense. For a period of more than a month, we set out early in the morning and returned at dusk, and visited every peak on Wutai Mountain. In my memories from that period, apart from the temples and the mountain paths, are memories of us constantly walking. Sometimes, in order to go to a temple hidden in the folds of the green mountains, we had to walk several dozen kilometers in a single day.

▲ Wutai Mountain

During that time, we made pilgrimages to all the temples of Wutai Mountain, and knelt before all the Buddha images, and turned all the sutra wheels, and circumambulated all the stupas. We left the footprints of all our yearning, and we used all our sincere reverence to feel the atmosphere of every blade of grass and every tree that was there.

My father later said that the great vows he made on Wutai Mountain during those days were later all fulfilled.

Those days were serene and happy. We put all worldly complications behind us, and on one little path after another, on one quest after another, we savored the simplicity and cleanness of the mind and spirit. Every patch of sky was clear blue for you. Every mountain breeze was pure for you. Every tree was fresh and strong for you. Every temple was waiting for you to keep your appointment.

Keep going and going, from the previous lifetime to the next lifetime!

With my father, I made pilgrimages to many holy sites, like Labrang Monastery [in Gansu province], Ta’er Temple and Xia Qiong Temple [in Qinghai province], Xiang Xiong Temple…. Almost every one of these places became a pure land in my mind.

Our family’s most recent pilgrimage was to Tibet.

This is a place that I had dreamed of but had never dared to encounter directly.

In the book [The Alchemist, by Paulo Coelho, known in Chinese as] Fantasy Travels of a Shepherd Boy, the shopkeeper of the crystal shop said it this way: “Because Mecca supported my hope to keep on living, and enabled me to bear the ordinary times, and put up with the crystals in the cabinet that could not talk, and put up with those lunches and dinners in awful restaurants, I was afraid to make my dreams come true. After they came true, I would have no more impetus to keep on living…. So I would rather just hold onto it as a dream.”

I had this kind of feeling about Tibet. I was afraid I would lose hope and I would destroy the dream that I had built up for so long. The Tibet in my mind belonged only to me; it was my sacred land, with no connection to anyone else, no connection to the outside world, and no connection even to the real Tibet.

▲ Tibet

But I had decided to go on a pilgrimage. This world has no lack of dreamers. What is lacking are people to revere the truth with their actions and to put the truth into practice. What’s more, many scenic places require you to go there in person and touch them, and only then can you feel their spirit.

Thus, snowy mountains, Buddhist temples, holy lakes, like old friends keeping an appointment, walked into my life surrounding with the natural greatness of a soul -- magnanimous.

When I returned from the pilgrimage, I suddenly became conscious of that fact that the destination of the pilgrimage may not be what is most important. What is most important is that you must have the mind of pilgrimage, and then use the action of going on the pilgrimage to purify your own spirit. Later, my father said that, from the point of view of the ultimate truth, all his activities were in fact being on a pilgrimage.

Some time later I read Biographies of Eminent Monks and Great Worthies through the Generations. Many of the eminent monks and great worthies in it climbed mountains and crossed rivers in order to spread the Dharma, or to get the Buddhist sutras. I thought: these arduous journeys are a part of cultivating practice.

The years flow by like water, and the things of the world change and shift. After I grew up, I had my own understanding of the Buddha Dharma. What was muddled at first became a clear, lucid yearning. I particularly like a statement of my father’s: “Genuine faith is unconditional. It is just a certain spiritual reverence and yearning. Faith is not a means for seeking merit and reward, faith itself is the goal.”

I have spent two years editing the text in such books as The Ever-bright Mahamudra:Instant Enlightenment. These books are a recording of my father’s everyday conversation. He explains to me a thousand years of wisdom which Buddhism has passed on, and he resolves all the questions in my mind about death and life. It was as if I turned around for an instant, and suddenly everything before my eyes emptied through and was clarified, and I saw a scene which I had never seen before.

The road I must travel from here on is even more clear and solid. I think back on the scenes from when we were on pilgrimage, and at the end of a faraway, rugged mountain road is a temple smiling into the wind.

(To Be Continued...)