My Father Xue Mo and I (6)

By Chen Yixin

translated by J. C. Cleary etc.

Part Six

My father and I have gone through several important deaths together. Every time I went through one of these deaths, I was always left feeling utterly exhausted. They were like an evil laugh behind me on a dark night. They were rope in a deep seam in the earth. They were a fierce fire burning up people’s hearts and lungs. They left me afraid and uneasy. They made me feel a wrenching hopelessness.

The first to leave the imprint of death on my life was my uncle's. He was a young man of twenty-seven when he was buried in the yellow earth. His name was Chen Kailu. What he left me was only a few fragments. I couldn’t even remember anything that he had completed. His existence was like a dream from which a person is awakened with a start halfway through.

My earliest, clearest memory of my uncle is after he became ill. At that time, the operation for his late-stage liver cancer had failed, and so he had returned home. He lay on the kang, and his whole face was a waxy yellow, and his stomach was intensely bulging. I stood in the corner, having just come in, and looked at him from afar, and did not dare come closer. He waved to me, and asked me to come over. I shook my head no, because I was trapped by a nameless fear. I saw that when anyone mentioned my uncle’s sickness, there was always a look of catastrophic terror showing in their eyes. Later on, no one wanted to mention it, and this was like a wound that there was no way to heal, and even if you lightly touched it with your finger, it would release a pain that made people tremble non-stop. When my uncle saw that I would not go over to him, there was a look of gloom in his eyes, and I saw that he was very lost. When I think back on this moment, it is very hard for me to bear. Even now, I cannot forgive myself for this behavior, and I don’t understand why a five-year-old child would be so cold and indifferent.

Again I looked at him, and we were already worlds apart.

In an essay I wrote this:

I remember that morning very clearly. In the clean glass of the window of the kindergarten, my mother’s grief-stricken face appeared. She had a few words with my teacher, and after that the teacher turned around and said, “Chen Changfeng, collect your book bag, and go home with your mother.”

As soon as we entered the gate, the sound of crying filled the courtyard. I was scared stiff and stood terror-stricken where I was, and for a long time my spirit did not return. With these adults I had originally seen as big and strong all crying with grief, I was terrified. Later, when my uncle was put in his coffin, I saw his discolored face. That face was branded on my soul from then on.

When I think about this now, what had the greatest impact on me then was not my uncle’s death in itself, but rather how people looked after his death, or to put it accurately, how my father and my grandmother looked.

My father had been with my uncle during the last few months of his life, and he watched helplessly and saw how a strong man could be buried in the ground. The look of grief on his face brought a deep stabbing pain to my heart, because I had never seen him this way before. The day of sending out obituary of my uncle, my father shut himself up in a little room, and wrote a long eulogy.

My uncle’s early death directly changed my father’s life. For a few years afterwards, he began to ponder death, and he put a skull in his bedroom, to constantly alert himself to how easily life passes away. Once he pointed to that skull and said to me: “He or she may have once had talent, or may have been rich, or may have been good-looking and elegant, but now none of this is important anymore. What is important is whether or not he or she completed the work that he or she had to do, before death caught up with him or her.”

If my father’s reaction alarmed me, then my grandmother’s reaction terrified me.

I wrote about it like this:

The night before my uncle was buried, it was very windy. A Taoist priest brought nails and began to nail up the coffin in the courtyard. Grandmother, who by this time had already become feeble, suddenly rushed like the wind over to the coffin, desperately wanting to open it up and see my uncle. People forcibly picked her up and carried her into the house, but where her fingernails had scratched the coffin, it left deep marks.

The next few nights were hopeless and endless. Grandmother’s mournful howling went on without stopping, and this howling was transformed into all of life’s hopelessness and helplessness, and floated out into the dark wilderness.

For several days I did not dare go into my grandmother’s room, or dare to look at my grandmother’s face. I stood in the bustling courtyard, and her hoarse cries came out through the window, blending with the noisy sounds of the suona horns, and became a drill piercing my heart again and again.

Though the courtyard was full of people, it exuded a kind of desolation it had never had before. I was constantly feeling a vague pain in a certain place in my body, as if there was a wound that was deep, though not bleeding. I do not remember what the weather was like then, but in my image of it, the whole sky was yellow, the sun was pale and dim, and a cold wind was blowing in the sky. No matter how thick the clothes I put on, I was chilled to the bone.

The next day, I went with my father and mother to the gathering at the grave. In the flight of the yellow earth as it was shoveled into the grave, I realized that this was the endpoint of every life, and no matter how you try, no one can escape it.

If my uncle’s departure gave me my first impression of death, the demise of Master Wu was my most close-up feeling of death.

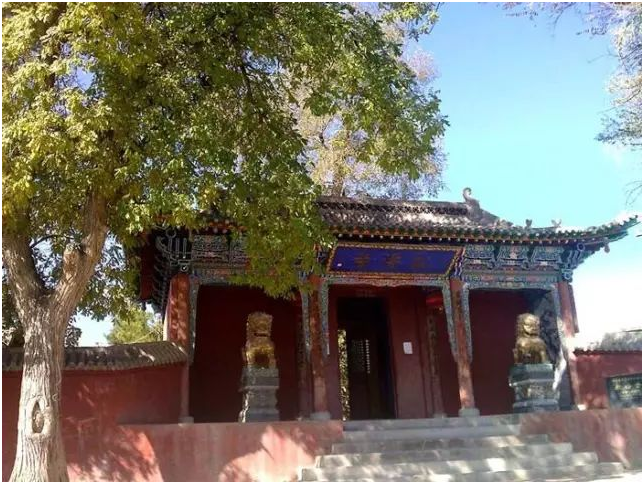

Master Wu’s original name was Wu Naidan; he was the abbot of Song Tao Temple in Liangzhou. My father had taken Master Wu as a basis for more than twenty years, and received from him many precious teachings of Shangpa Kagyu Buddhism. When I was little, I would often go play in the temple, and from time to time he would teach me a few things.

Song Tao Temple had previously been a temple in name only, and there were just a few adobe houses. I had heard my father say that the great hall and the Buddha-images had been destroyed during the “Cultural Revolution.” So Master Wu’s greatest wish was to rebuild Song Tao Temple.

▲ Song Tao Temple, today

Master Wu’s master was called the “Monk Shi.” He was a famous martial arts master in Liangzhou. His level of attainment was high, and he was very fierce. He was the real-life prototype of “Papa Jiu” in my father’s novel Curse of Xixia, and also of the “Monk Shi” in The Grey Wolves of the Western Xia. Even today, the old men in the streets of Liangzhou still take delight in telling wondrous tales of his martial arts prowess. When I was eighteen and an admirer of the martial arts, I took a famous martial artist in Liangzhou as my teacher and heard many stories about the Monk Shi. In theory, Master Wu must have been a martial arts expert too, because he was the only disciple of the Monk Shi. But in fact it was just the opposite, and Master Wu knew nothing about martial arts. And this was not because the Monk Shi had been stingy about sharing his knowledge, but rather because Master Wu thought that studying martial arts was without meaning, and was not the ultimate level, and would waste his life. I felt sorry about this for a long time.

In order to repair the temple, Master Wu subsisted for years on boiled water and dried buns. These buns were donated to the temple by the congregation twice a month.

When Master Wu was nearly seventy, Song Tao Temple finally began to take shape.

Before Master Wu passed away, our family went to see him.

Song Tao Temple was serene and quiet as usual, and the great hall was empty and lonesome, filled with the atmosphere of Zen study. On the floor in front of the Buddha-image there was still that worn-out meditation cushion. The hundred-year-old pine trees in the courtyard were still vigorous and strong, standing upright through the vicissitudes of time. They had seen through the human world, with its sorrows and joys, it separations and meetings, and were already indifferent: they had become Bodhidharma facing the wall.

Master Wu used all the money he had to repair the temple, and basically paid no attention to the fact that he himself was already a seventy-year-old man, and paid even less attention to his undernourished body. He had truly achieved a selfless state.

On the way home, my father told me: “A person’s value is the sum of his actions, and Master Wu is an amazing eminent monk.”

One week later, in Song Tao Temple, Master Wu went to sleep forever. Every hall he had built, every wall, every stair, silently accompanies him, and tells of his greatness.

On the day Master Wu was cremated, my father and I came early to the site. The sky had not yet fully brightened, and a fine drizzle was coming down. Before, I had thought that the cremation ground must be very gloomy, and I had not realized that it would be extraordinarily quiet and still, and there would actually be the feeling of being in a temple.

At daybreak, the masters from other temples came to perform the ceremony, and the sounds of the music and the chanting and the crying all blended into one, and fused into the ethereal in my heart.

When the ceremony was completed, the cremation began.

There was a small opening in the crematory oven, and you could see what is was like inside the oven. My father had me stand in front of that small opening and watch what a life returns to.

This let me understand that life is a joke, a joke played arbitrarily by the gods.

I felt heaven and earth turning, and it was like falling, falling endlessly….

For a month after this, I was dispirited and wandered around like a ghost. Burning bones appeared constantly before my eyes. At that time the sunlight was covered by black clouds, and my emotions were withered by the cold wind. The world was an abandoned castle, dark, dead quiet, boundless, for a thousand years.

I suddenly understood the “impermanence” which the Buddha had spoken of, and felt the hopelessness behind the impermanence that makes heaven and earth collapse. That’s it then: the myriad things, heaven and earth, finally come to the same end.

At that point in time, I could not find a reason for living, and I felt that the world had no meaning, and life had no meaning, and nothing had any meaning. During that time I did not write anymore, I did not read books anymore, I did not cultivate Buddhist practice anymore, I did not have joy and anger and grief and joy anymore. I had seen the end: the end of heaven, the end of life, the end of the world.

My father saw all this in his eyes. He explained to me the Verses on the Genuine Cultivation of the Mahamudra, and asked me to organize the transcript of his book. My father’s Mahamudra wisdom let me realize a true spiritual sublimation.

After several months, I slowly emerged from the morass of hopelessness, and I was no longer tangled up in nihilistic empty nothingness. Having gone through this experience, I again saw this familiar world as especially vivid and clear.

Yes, Master Wu had passed away, and his remains had been cremated. But the temple that he had repaired was still there, and the spirit that had repaired the temple was still there, and the teachings and wisdom that he had imparted to my father were still there. This spirit would be passed on, and this wisdom would be passed on, and would influence more people. Maybe this would also become my meaning and purpose for living.

That fire also burned up my many clingings and attachments, and let me seriously ponder my own life. I’m always wondering whether or not, many years from now, when my own body enters the flames to be cremated, I will be able to leave something behind that the fire will not burn up.

In later years, when I was wasting my life or criticizing myself or others, then I would think of that crematorium. When I was entangled in clingings and attachments, I would think of that crematorium. When I was at a fork in the road and unable to choose, I would think of that crematorium even more. Though it does not make a sound, it is always rumbling in my life.

At this point, my father had taught me something he had wanted to make me learn – using his wisdom and his actions.

I will follow in my father’s footsteps, and go forth on my own path.