Appendix: Listening to the Voice of Wisdom

On the Illumination of the True Mind from My Experience as a “Calligrapher”

All the genuine works of art in the world are the products of the true mind and great love. In the arts, once you have a tricky mind, your true mind will retreat accordingly. Your true mind and tricky mind are like the yin-yang fish in the diagram of taiji. When yin waxes, yang wanes. The farther away from the true mind, the farther away it is from the true spirit of the arts.

The sudden enlightenment of my “graffiti” came from one little incident.

At that time, a temple in Canada launched a magazine to propagate Mahamudra, and they asked me to be the editor in chief. The title of the magazine would appear on the cover in both English and Chinese. The English title wouldn’t be a problem, but the Chinese one had to be taken seriously. So I had planned to invite a calligrapher in Zhejiang to write it. Over eighty at that time, that calligrapher cares about nothing outside the body except calligraphy and painting. Using his handwriting as the title of our magazine would be in the spirit of Mahamudra. So I prepared some remuneration, transferred it to one of my friends, and asked him to visit the calligrapher for me. The old man took the matter seriously and practiced quite some time before he produced a piece that he was satisfied with. This piece must be extraordinarily good; otherwise, my friend wouldn’t have kept it for himself. Although I was a little disappointed about not being able to see the writing, I couldn’t ask that calligrapher for his work again, for I was afraid that the old man would be angry at my friend’s doing and that their friendship would be affected. I had planned to prepare another remuneration and contact some other calligrapher, but, as I prefer simplicity in art, I don’t think highly of the works out of the tricky mind of established artists. However, the magazine couldn’t do without a title. So I thought I might do it myself.

Then, I bought several quality brushes and some quality xuan paper, and, shutting my door and switching off my mobile phone, like a Chan practitioner going into retreat, I started to scrawl by following my mind.. On the first day, I relied on my aesthetic cultivation as a writer and tried very hard to produce something good. After many trials, I produced a few pieces that I was really proud of. However, on closer examination, those pieces which looked quite impressive at first sight turned out to be affected and insincere. The same is true of my “literary works” before A Cult of Vast Desert.

The next day, I decided not to practice calligraphy. I shattered all artificial cultivation and wrote away at will, disregarding any rules and principles. Seeing the xuan paper filled with ink spread all over the floor, my son asked, “Dad, what are you doing? It is disrespectful to say you are wasting paper, and you don’t seem to be a wealthy man. So, what are you doing now?” I said, “I’m trying out the nature of the brush, the paper and the ink.” “What then?” he asked. “After I can control the brush and ink so that they follow my mind,” I replied. “My true mind and great love can flow out.”

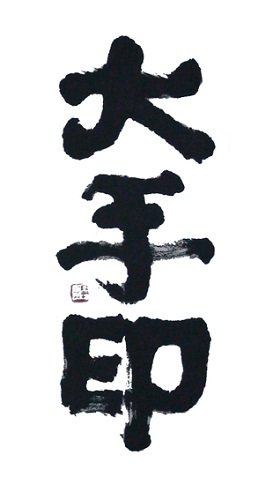

Believe it or not, several days later, the brush and ink became a tamed bull, heading east or west according to my directions, and any of my mental state could be expressed in ink. Thus, I became merged into the true mind – clear, bright, and void of anything – which is called, in spiritual practice, “ever-bright Mahamudra.” In that state of mind, I wrote the three Chinese characters Dashouyin. Upon seeing it, my son exclaimed, “Superb work!”

From that moment on, I remembered, I became a “calligrapher.” The experience was quite similar to that of my practice before I wrote A Cult of Vast Desert. The difference is that I spent five years practicing writing. After I mastered it, I was able to free myself of the mark of words.

After the flash of genius, I got rid of all concepts of calligraphy. I forgot brush and ink, I forgot aesthetics; effortlessly, I maintained that state of mind, without attachment or detachment. Making use of the marvelous function of the profoundly empty mind, which was free from affectation and artificiality, I drove the brush as I pleased, forgetting both the self and the object, returning to simplicity and sincerity, to express the great good and great love in my mind. The next day, the three characters Dashouyin I wrote seemed to be alive with supernormal powers and infinite charms. A veteran calligrapher in Liangzhou exclaimed, “Marvelous! Extremely simple and naive, yet charged with infinite powers.”

I mounted a few pieces to see the effect, and they were praised by all the viewers.

Later, Mr. Zhuang Yinghao, the famous assessment expert in Shanghai, judged that the characters Dashouyin I had written represented both in appearance and in spirit the Mahamudra culture I have been advocating. The character da (great) is energetic and full of power, stretching toward infinity and suggestive of greatness, magnificence, infinity; it symbolizes great realm, great generosity, great vows, great kindness without cause, and great compassion based on sameness in essence. The character shou (hand) is surely a marvelous function of the true mind; it represents gesture, movement, behavior, being mundane, and all kinds of dependent arising and phenomena. The character yin (seal) looks upright and plain, without affectation. Aiming at the original enlightenment, spontaneous, and fully aware of the great way, it symbolizes the mind-seal of buddhas, i.e., the illuminating and empty wisdom, which is the inherent supramundane wisdom. The three characters combined encompass all the physical and mental phenomena of both the mundane and supramundane world. Da is the root, shou the way, and yin the result. None is dispensable. Without a “great” realm, “hand” and “seal” can only attend to their own businesses and great power is not likely to be generated from them. Without the behavior of the “hand,” “greatness” tends to be rendered to empty talk. Without the realization of the “hand,” the “seal” tends to be reduced to mad wisdom. Without the illumination and emptiness of the “seal,” “greatness” and “hand” are reduced to mundane dharma. “Greatness” and “seal” become meaningful only when they are incorporated in the behavior of the “hand.” Mahamudra (great hand seal) without behavior that benefits sentient beings is not genuine Mahamudra.

Mr. Zhuang believed that all those unique conceptions in the Mahamudra culture I have been propagating are epitomized in the characters Dashouyin I write.

Now that I was able to commit my enlightened, marvelous true mind to brush and paper, I selected some pieces and gave them as gifts to the friends who had helped to have good books printed. I didn’t expect that this would bring a big deal. A boss doing culture business wanted to sign a contract and purchase a hundred pieces I wrote with a large sum of money. He promised that he would promote my Mahamudra calligraphy on condition that I must stop giving my work to others for free. I talked with Mr. Zhuang and thought such a monopoly would prevent those friends who had helped with the printing of good books from getting my calligraphy. Therefore, I turned down the boss.

I once asked one of my friends in Guangzhou why he liked my Mahamudra calligraphy. He told me that an expert said that there was illumination from my naïve and simple writing, as if it had been blessed by eminent monks. The friend also told me that someone had my calligraphy mounted and sent to friends as precious gifts. He said that things with illumination could carry messages of the good and the beautiful and bring peace, coolness and auspice.

I just smiled at those remarks.

I said, “Do you take me for a Taoist priest who draws magic figures?”

I have never considered things outside of the mind to be more important than the simple and naïve true mind.

But a monk friend who had got an glimpse of the essence of spiritual practice smiled and said, “Isn’t the purpose of the Taoist priest chanting spells and drawing magic figures to find the true mind and great good? After he has acquired the true and the good, his vermilion brush is able to correspond with Nature. And the enlightened and marvelous true mind will give out light according to conditions and bring enormous benefits. The secret of drawing magic figures is none other than that. As to the crooked black and red ink traces, they are not important.

I can see the truth of his remarks. When I am doing calligraphy, there is neither phenomena nor the self, which is quite similar to the situation when I was writing A Cult of Vast Desert, The Hunting Ground, and White Tiger’s Gate. What I have done is get rid of artificiality, affectation, the tricky mind, and all other pretenses, and let my unaffected true mind and great love flow out spontaneously.

Could it be the secret of art?

Or, is a genuine work of art a marvelous function of the true mind?

Perhaps, just as my friend said, things that flow out from the true mind really give out light. Of course, I’d rather treat it as a symbol. In the world, the most precious things are great love and the true mind. To a certain extent, they definitely “give out light.” I find that all the genuine works of art in the world are the products of the true mind and great love. In the arts, once you have a tricky mind, your true mind will retreat accordingly. Your true mind and tricky mind are like the yin-yang fish in the diagram of taiji. When yin waxes, yang wanes. The farther away from the true mind, the farther away it is from the true spirit of the arts. That is why Tolstoy has always occupied the highest position in world literature, for he managed to use simplicity to communicate great good, great truth, and great beauty.

Great love and the true mind, if they are genuine, certainly can carry the illumination we need.

Sometimes, when we are in the dark night, the weak light from a small flashlight will pierce the darkness. Light, no matter how weak it is, is able to penetrate the seemingly powerful dark night.

In my eyes, the light of the true mind is a spirit borne by the arts.

Notice

Translated by non-professional volunteers, there would be some inaccuracies in the translation. You are welcome to offer us some advice for emendation. Please feel free to contact us.We also look forward to you joining our voluntary translation team.

Please contact us at 985140751@qq.com, thank you.

附录:聆听智慧的声音

从我的“墨家”经历谈真心的“光”

世上所有的艺术真品,无一不是真心和大爱的产物。在艺术中,要是你一旦有了机心时,真心便会相应淡化。真心和机心,永远像那个太极图上的阴阳鱼。阴盛时,必然会阳衰。真心越淡,离艺术真正的精神越远。

我对涂写“墨迹”的顿悟,源于一件小事。

那时,加拿大某寺院创办了一本杂志,弘扬大手印文化,想请我当主编。杂志用中英文两种字题名,英文可随便,中文却不敢含糊。于是,我便想请浙江某书家题个刊名。此老年过八旬,对身外诸物,大多了无牵挂,所系心者,止书画耳。以其字作为刊名,想来会有点大手印的神韵。于是,我筹了润笔费,打给友人,托他代往求字。老人很认真,练了许久,才拿出一幅满意的字。想来这字,定是神品,否则,友人不会心爱不舍,自家收藏了。虽然那幅至今我未曾谋面的字带给我些许失望,但我不能再向老人求字了,怕友人之爱,惹老人生气,会影响到他们日后的相交。有心再筹资他求,但我又喜欢拙朴,对名家的机心之作,总不随喜;而那杂志,又不能不用刊名,便想,还是我自己写吧。

于是,我购得好笔数支,好纸若干,闭门谢客,关了手机,效法禅家闭关,由心涂鸦了。头一日,我运用作家的美学修养,想着力写出好字,涂抹多了,竟然也写出了几幅叫我洋洋自得的“书法”来。不过,猛一看张牙舞爪,细品却露出原形,显出诸多的机心和造作来。这一点,跟我写《大漠祭》前的那些“文学作品”相似。

第二日,我决定不再练书法了。我打破所有的人为修养,整日里昏天黑地,乱涂乱抹,信马由缰,不辨东西南北。看着我涂染了满地的上好宣纸,儿子问:“爸,你在做啥?说你浪费纸吧,有些不敬;说你财大气粗吧,似乎不是;你在做啥哩?”我说:“我在掌握笔性、纸性和墨性。”他又问:“掌握之后又将如何?”我说:“笔墨随心之后,再流出我的真心大爱。”

嘿,数日之后,那笔墨竟成了驯熟的牛,指东便东,指西便西,点滴心绪,皆可入墨。于是,我便融入那种朗然光明、湛然无物的真心状态——在心灵修炼中,此种境况被称为“光明大手印”,写了“大手印”三字,不成想,儿子大叫:神品!

记得,从那一刹那起,我便成了“墨家”。这一过程,跟我写《大漠祭》前的练笔相若。不同的是,那时的文学修炼,竟然用了整整五年。当我的文字修炼得心应手之后,我便破除了所有的文字相。

灵光乍现之后,我便远离了所有的书法概念,忘了笔墨,忘了美学,任运忆持,不执不舍。妙用这空灵湛然之心,使唤那随心所欲之笔,去了机心,勿使造作,归于素朴,物我两忘,去书写心中的大善大爱。一天过去,那“大手印”三字,便如注入了神力,涌动出无穷神韵了。凉州一老书法家叹道:好!拙朴之极,便又暗涌着无穷的大力。

我试裱数幅,看看效果,观者皆称妙。

后来,上海著名评估专家庄英豪先生认为,那“大手印”墨迹从形神几个方面都代表了我所倡导的大手印文化:那“大”字,精进而充满活力,其神其势,伸向无穷,有伟大、雄伟、无尽、无限之神韵,它象征大境界、大胸怀,大心大愿,无缘大慈,同体大悲;那“手”字,分明是真心生起的妙用,代表姿态、运动、行为、入世以及诸多缘起和现象;而那“印”字,端方质朴,去机心,事本觉,任自然,明大道,象征佛之心印,系明空智慧也,代表出世间的本体智慧;这“大手印”三字,便能涵括所有出世入世及心物现象。“大”为根,“手”为道,“印”为果,三者缺一不可:没有“大”的境界,“手”和“印”只能自了,难生大力;没有“手”的行为,“大”易流于空谈;没有“手”的体现,“印”便易成狂慧;没有“印”之明空,“大”和“手”便沦为世间法了。“大”、“印”只有体现在“手”的行为上,才有意义。没有利众行为的大手印,便不是真正的大手印。

庄英豪先生认为,我上面倡导的那种独有的大手印文化理念,全部体现在“大手印”墨迹中了。能将那妙明真心诉诸笔端之后,我便选出多幅,赠予助印善书的友人。不成想,这一赠,竟会招来大宗的“买卖”。一文化产业老板欲以重金购买百幅,并想跟我订合同,说以后我的大手印墨迹由他包装推销,只是他有个条件,我不能私自送人。我跟庄先生商议之后,觉得他这一专营之后,我的那些助印过善书的朋友便无缘再得到我的墨迹了。于是,我拒绝了他的专营设想。

我问广州朋友,为啥他喜欢我的大手印墨迹。他说,一位识家称,那拙朴的字有光,有种“开过光”的灵气和神韵。他说有人便将那墨迹装裱,作为珍贵礼物,作为赠送朋友的礼物。他还说,有光的东西,能承载一种善美的人文讯息,能给人带来安详、清凉和吉祥。

对此说法,我只是一笑。

我说,你们以为我是画符的道人呀?

我从来不认为那些心外的东西,会比拙朴的真心更重要。

但一窥得心灵修炼精髓的僧友却笑道:那些道人念咒呀画符呀,不也是为了寻找真心和大善吗?得到真善之后,一点朱砂妙笔,便与造化相应了。那妙明真心,自会随缘放光,带来无穷大益。那画符的秘密,便是如此,至于那歪里邪里的红黑墨迹,并不重要。

对这一说,我倒是心领神会。是的,我涂墨迹时,也跟写《大漠祭》、《猎原》和《白虎关》时相若,真的是无“法”无“我”了。我仅仅是去了造作,去了机心,去了一切虚饰,而流淌出自己无伪的真心大爱而已。

莫非,这便是艺术的奥秘?

或者说,那真正的艺术,便是真心的妙用?

也许,真像朋友说的那样,真心流淌的东西会有光的。当然,我更愿意将此说当成一种象征。这世上,最珍贵的是大爱和真心,从某种意义上来说,它们肯定会“放光”的。我发现,世上所有的艺术真品,无一不是真心和大爱的产物。在艺术中,要是你一旦有了机心时,真心便会相应淡化。真心和机心,永远像那个太极图上的阴阳鱼。阴盛时,必然会阳衰。真心越淡,离艺术真正的精神越远。这便是用朴素承载了大善和大真因而也是大美的托尔斯泰永远高居世界文学顶端的原因。

真正的大爱和真心,定能够承载我们需要的光明。

在我的眼中,那真心之光,便是艺术承载的某种精神。

有时,当我们身处暗夜的时候,哪怕打亮一个小小的手电筒,那微弱的光,也会刺破暗夜。光,无论多么微弱,总能刺穿看似强大的暗夜。

声明:本文系文化志愿者试译,非专业人才翻译,错误定然不少,如出现疏漏及错误,敬请读者见谅。如有任何翻译上的建议及修正意见,欢迎及时与我们取得联系,我们会加以校对、修改,并希望有专业才能的朋友也能加入我们志愿者群体中来。

邮箱地址:985140751@qq.com