|

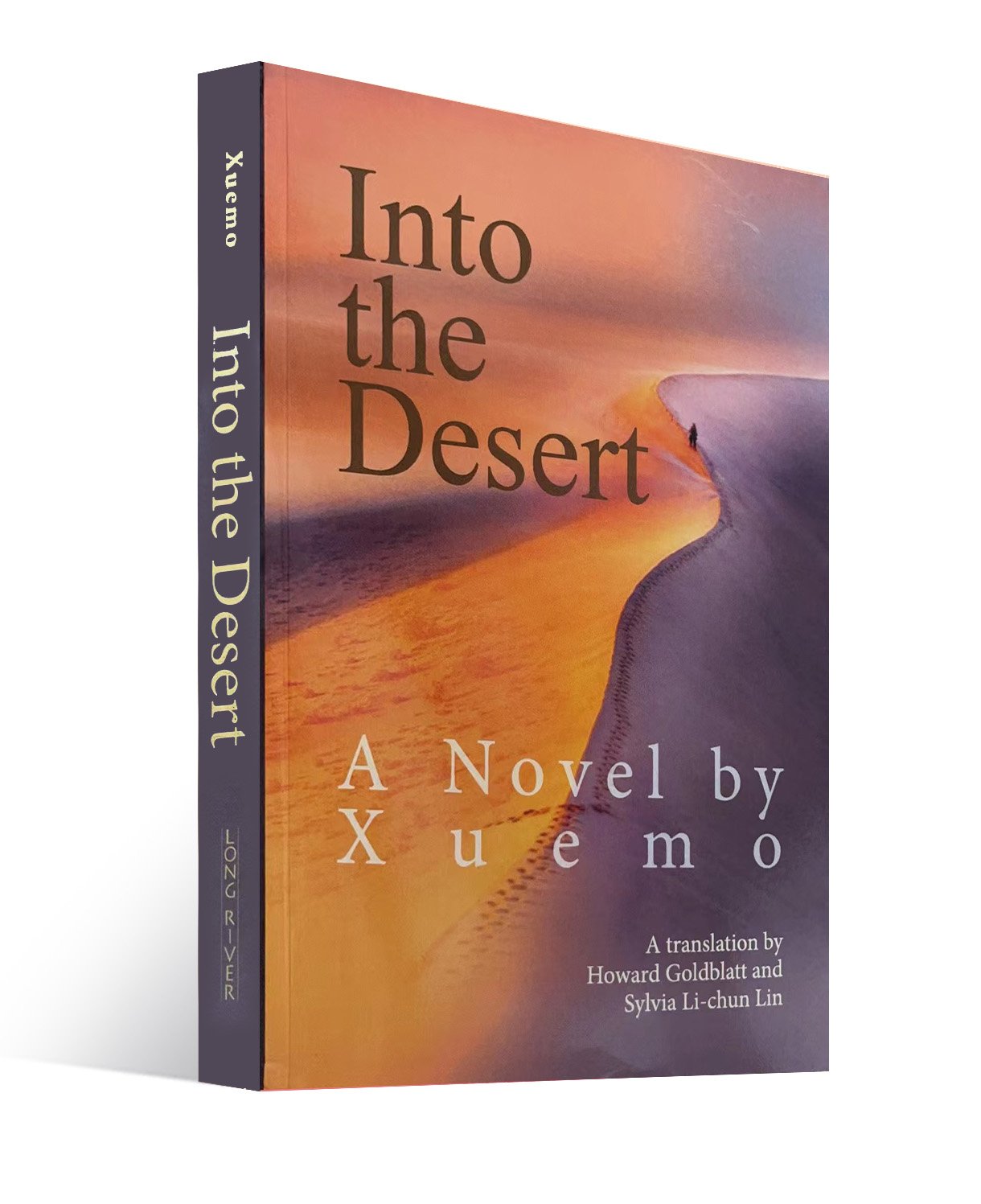

Into the Desert

Review by James Kennedy

In mid-1990s rural China, two sisters-in-law set upon a dangerous journey in Xuemo’s compelling novel Into the Desert (Long River Press). There aren’t many choices beyond marriage for pious, practical Lanlan and sweetly idealistic Ying’er in their poor village on the edge of the Gobi Desert. In an economic exchange arranged by their mothers, the two women are paired off with one another’s brothers, but this turns out to be a raw deal for both brides. In defiance of custom, feisty Lanlan walks out on her marriage to Ying’er’s older brother Bai Fu—an abusive lout who abandoned their young daughter to die in the desert, superstitiously believing this would eventually cause Lanlan to bear him a son in her place. Ying’er, in turn, is married to Lanlan’s hapless brother Hantou, who promptly dies of liver cancer—but not before callous city doctors drain the family of their savings. Lanlan’s breach of the families’ exchange marriage agreement means that either Ying’er must be forced to marry again, or they must find another wife for Bai Fu. The two sisters-in-law hit upon a third option: journey across the desert to the salt lakes, and bring back a load of valuable salt to buy Ying’er’s freedom.

Traveling light, Lanlan and Ying’er set off on camels to the Mongolian border. Lanlan optimistically predicts the journey will take only a few days. The sisters-in-law look forward to it as a relief from village gossip and family pressure. “They knew how happy and free they would be out in the desert,” writes Xuemo. Then, ominously: “They could not have been more wrong.”

What follows is a gripping story of survival in the wilderness, in which the grit and resourcefulness of Lanlan and Ying’er are tested to the breaking point. As in all great adventure stories, Xuemo ably convinces the reader, time after time, that the sisters-in-law have exhausted all their options and face certain death. But again and again, he finds unexpected but plausible ways for them to survive—though not without paying a heavy price.

Both women bring their peculiar strengths to the journey. Lanlan is the more obviously resourceful, active, and knowledgeable of the pair: she can handle a gun, skin a camel, and identify edible desert plants. A devoted Buddhist, her bravery is entwined with a certain fatalism. “If you really have to die,” she shrugs at one point, “it’ll happen whether you’re afraid or not.”

Ying’er is more passive and circumspect but with hidden reserves of nerve and tenacity. When Lanlan is bitten by a poisonous snake, Ying’er unhesitatingly risks her own life by sucking out the poison from Lanlan’s arm. When Lanlan too readily accepts her fate in a sand pit that threatens to bury her alive, Ying’er refuses to give up, and stubbornly finds a way to save her. One senses that neither could make it on their own. They make an appealing pair of unconventional adventurers. Even in grim circumstances, they find ways to make the unbearable bearable, such as when they both playfully slide down a sand dune: “For years, they’d lived under the gaze of others; this was the first time they’d been able to let go, and they were surprised to rediscover their inner girlhood at a time and in a spot where they were about to abandon all hope.” Lanlan and Ying’er are engaging, vulnerable, and recognizably human, even for readers whose circumstances are far removed from the poverty and social customs of rural China. You can’t help but root for the pair to succeed, even as you suspect the worst is to come.

Into the Desert focuses on the sisters-in-laws’ deepening relationship as they come to rely on each other in their perilous journey. Thrilling episodes of desert escapades are interspersed with vignettes of their lives beforehand—the ups and downs of rural village life, with all its romances, frustrations, victories, and humiliations—and we soon understand why both are desperate enough to make this risky venture. Although Into the Desert is packed with plenty of riveting action—a hair-raising showdown with a pack of jackals makes for a bravura extended set piece—we find ourselves truly learning to care for our heroines through these flashbacks to their ordinary lives.

Both women have private sorrows that only complicate their close relationship. Ying’er’s infant son, whom she left with her mother-in-law to embark on this journey, wasn’t actually sired by her impotent husband Hantou, but rather his passionate brother Lingguan—Ying’er’s true love who left town in self-imposed shame after his cuckolded brother succumbed to cancer. And Ying’er reaches the last straw when her poverty-stricken parents prostitute her, without her knowledge, to the village matchmaker. Her sister-in-law Lanlan fares no better, though: Ying’er’s brother Bai Fu beat Lanlan mercilessly—by fist, by whip, by thorny branch, by whatever came to hand—and even went so far as to pour salt into her wounds afterward. This treatment strains even Lanlan’s stoical attitude. “I realized that I died whether I fought back or put up with it,” Lanlan muses after she reveals to Ying’er the full extent of Bai Fu’s mistreatment. “But we aren’t born to be whipped.”

Xuemo vividly and unsentimentally depicts rural village life in China as an endless struggle of grinding labor, submission to customs, and exposure to predation. A blow-by-blow account of how Ying’er’s husband Hantou becomes ill, endures the humiliation of visiting the nearby city for medical treatment, and must submit to an unsuccessful, unnecessary, and ruinously expensive operation is a heartbreaking account of futility. Xuemo pulls no punches here, allows no facile hopes, offers no easy answers for these bleak circumstances. This is simply the way life works out here, the book seems to insist; and indeed, as the hardships pile up, Lanlan’s trademark resignation seems less hopeless, and more realistic. How much should we struggle against our circumstances, and reasonably expect to rise above them? On the other hand, how much should we simply accept our fate, and submit to what the world has allotted to us? Into the Desert considers the question from all sides, and while the book certainly has a fatalistic streak, it also makes room for a certain limited hope, for those prepared to pay the price.

It's not all grim. Ying’er’s and Lingguan’s secret love affair is sweetly and movingly described, a tender and all-too-brief romance. Every description of the famished sisters-in-law enjoying whatever meager sustenance they are able to scrounge from the desert reads like a delectable feast. And Ying’er’s and Lanlan’s friendship and trust in each other is a pleasure to read.

Xuemo puts his heroines through the paces in the desert, as they suffer hunger, thirst, losing their way, losing their camels, and getting attacked by various beasts. Every victory is short-lived, and the small prizes for which they sacrifice so much are usually snatched away. And yet, for all this adversity, Lanlan and Ying’er never lose hope, and never turn against each other. We trust in them to support each other through the challenges, through their ingenuity, endurance, and willingness to risk almost everything. We believe in them. We want them to succeed.

Our heroines do eventually cross the desert and reach their goal at the workers’ encampment at the salt lake. They find employment there, but also a set of new challenges, as they must negotiate the social hierarchies among their fellow immiserated workers and the petty bosses who take advantage of them. In this workers’ encampment, Ying’er’s good looks thrust her unwillingly into the jealousies and love triangles of the other employees and their supervisors—an odious scene of a “movie night” for the workers, in which the men grope the women with varying degrees of consent, is particularly dismal. Ying’er steadfastly resolves to save herself for Lingguan, hoping against hope to meet him again somehow. This seems unreasonably romantic to Lanlan, who can’t understand why Ying’er won’t accept the prosperous boss’s offer of marriage, and the comparatively easy life that would follow for both of them. The usually timid Ying’er responds to Lanlan’s practical advice in a way that shows she is just as tough, in her own manner, as her more conventionally capable sister-in-law: “When I was little, my pa bought me a jade pendant. I loved it. One day my brother spat on it to spite me, because he knew I couldn’t stand anything filthy. It was soiled, so I smashed it. Do you see what I’m saying? I know that living requires compromises. You have to go along with people and muddle through. But I can’t do this. We’re on earth for only a few decades, why can’t we lead a clean life? Something dirty can never be cleaned.” Even after this speech, Lanlan still can’t quite fathom Ying’er’s reasoning, but like a true friend, she accepts Ying’er’s decision—even when it means tremendous personal risk for herself. And to be sure, by the end of the book, we will see just how seriously Ying’er meant what she said.

For even after surviving the ravages of the outward journey, the ordeals of the salt town, and the hazardous return trip to their village, it turns out Ying’er and Lanlan are no match for the circumstances that they had attempted to escape. They return to the village with less than they set out with; what’s more, their social and familial troubles there have only grown more dire. (Needless to say in a book this hard-boiled, they fail to bring back any of that valuable salt.) But Lanlan and Ying’er have been transformed by their journey, and each finds solace and escape from the intolerable situation in the village in their own way. One realizes that a traditionally satisfying happy ending, as much as one might yearn for it, would betray the honesty of this story. “Yellow sand, local customs, violent husbands, and grueling labor were a corrosive fluid that ate away a woman’s feminine self,” Lanlan concludes about the other women of the village. “Without knowing it, they had lost their best qualities and been turned into crones . . . machines to cook, to reproduce, and to toil.” Lanlan and Ying’er each find their own alternatives to becoming a “crone,” but each alternative exacts its own price.

Reading the book as a middle-class American far removed from the social pressures, cultural mores, and physical jeopardy that Lanlan and Ying'er endure is a bracing experience. It is difficult at first to get one's head around the details of their marriages, which is described as "an exchange arranged by their mothers as the only way the poor could marry off sons without bankrupting their families." Even if the nuts and bolts of the arrangement might remain opaque for a typical American reader, Xuemo vividly describes the scheme's practical and emotional effects—especially when it drives Lanlan and Ying'er to take great risks to circumvent it. From the comfort of one's reading chair, one wonders if one would have the pluck to undertake a similar journey.

Lanlan's and Ying'er's superstitions are probably unfamiliar to most Americans, which make them all the more interesting. When Ying'er balks at eating snake meat, Lanlan chides her: "It's a delicacy, a gift from the Yellow Dragon. Try it or he'll be upset." Peculiar perhaps, but no more unfounded than the way most Americans "knock on wood" after saying something overconfident or avoid walking under a ladder. Similarly, a typical American reader might find the characters' (especially Lanlan's) frequent emphasis on submitting to fate to be remote from their own sensibilities. Many Americans prefer to think of themselves as active shapers of their own fates, rising or falling according to their own efforts; the dark side of this is an American tendency to entitled grousing when things don't go their way. The characters in Into The Desert do struggle and complain, but never in a petty way: Ying'er says of Lanlan's father, "Isn't he always saying he can take whatever the gods dole out to him? Who doesn't suffer in life? You take what they give you and try to hold on to your dignity." There is a dignity in yielding to the inevitable, although it might also read to some as defeatist or passive. That said, the ordinary middle-class American likely to read this book almost certainly has more privileges, advantages, and social mobility than the poor Chinese villagers it describes. Most Americans don't believe in fate with the conviction of Xuemo's characters, but that is as much as a function of material economic realities as it as of cultural structures.

The sexism that Into the Desert’s poverty-stricken women must face is relentless. Lanlan’s and Ying’er’s emotions are scarcely taken into account when they are married off to Bai Fu and Hantou. Sons are more economically and culturally valuable than daughters, so much so that Lanlan’s husband Bai Fu abandons their daughter to die in the desert, believing that this sacrifice to a fox spirit will lead to a son being born. And when the sisters-in-law find work at the salt lakes, it's not enough that the labor is physically demanding: they must also navigate the demeaning sexual politics of the place. When we learn late in the book that Ying’er’s parents have sold her body to the village matchmaker, we understand the desperation that causes Ying’er to make her fateful decision near the end of the book. It would be nice to believe that American women and girls don’t have to deal with sexism on this level, but in our particularly socially retrograde era, it’s harder and harder to make that case.

There are other jarring similarities to American life. Many Americans will recognize with bitterness the infuriating runaround that Hantou gets from the Chinese health care system. Although China officially has free public health care (unlike in the U.S.), Hantou's tests and surgeries are apparently not covered, and the doctors relentlessly extract money and time from him and his family with futile tests and surgeries. Hantou muses that "each IV drip amounted to drinking his parents' blood"—and when his family fails to bribe the right doctor, Hantou excruciatingly goes under the knife without anesthesia. To add insult to injury, the doctors don't bother to remove the tumor anyway. When Hantou remarks upon hearing of his diagnosis, "I'd just as soon get hit by a car and put an end to it," we are startled at first by his hopelessness, but by the end of his wretched journey we are tempted to agree. Like many Americans, the Chinese characters are at the mercy of economic forces and structures much larger than their individual efforts can navigate. Perhaps the attitude of "submitting to fate" makes sense.

Into the Desert is by turns thrilling, heartbreaking, tense, and tender. It is also frequently surprising: just when the desert adventures reach a point of maximum tension, the narrative often flashes back to the sisters-in-laws’ past life in the village, and just when you think you might’ve had enough of desert adventures, the story plunges you into the wholly new and grimly fascinating world of the work encampment at the salt lake, where the hardships and obstacles are completely different. Throughout the story, we feel the tension between a certain hardheaded pragmatism and the higher ideals of the heart. How much of our sensitivity must we sacrifice just to survive? And yet, after we’ve forfeited our more tender sentiments, how much is life worth living? Into the Desert skillfully navigates this problem with humanity, compassion, and the occasional humor. “Don’t cry if the sand buries me,” says Lanlan to Ying’er when all seems lost. “Tears are water too. You’ll have to conserve.”

Xuemo’s straightforward prose style, as translated by Howard Goldblatt and Sylvia Li-chun Lin, is clear and vigorous. He deftly weaves together the adventure story of the desert travels with the social reportage of rural Chinese village life and the emotional journeys of his characters, each of them caught in traps that they struggle to escape, with varying degrees of success. According to the translator’s afterword, Into the Desert is, in fact, an excerpt and adaptation of Ying’er and Lanlan’s story from Xuemo’s three-volume, million-word saga involving dozens of characters from this region and era. The translators promise more translations and adaptations from Xuemo’s larger work; if those adaptations are as thrilling, heartfelt, and uncompromisingly honest as Into the Desert, then English-speaking audiences have much to look forward to.

|