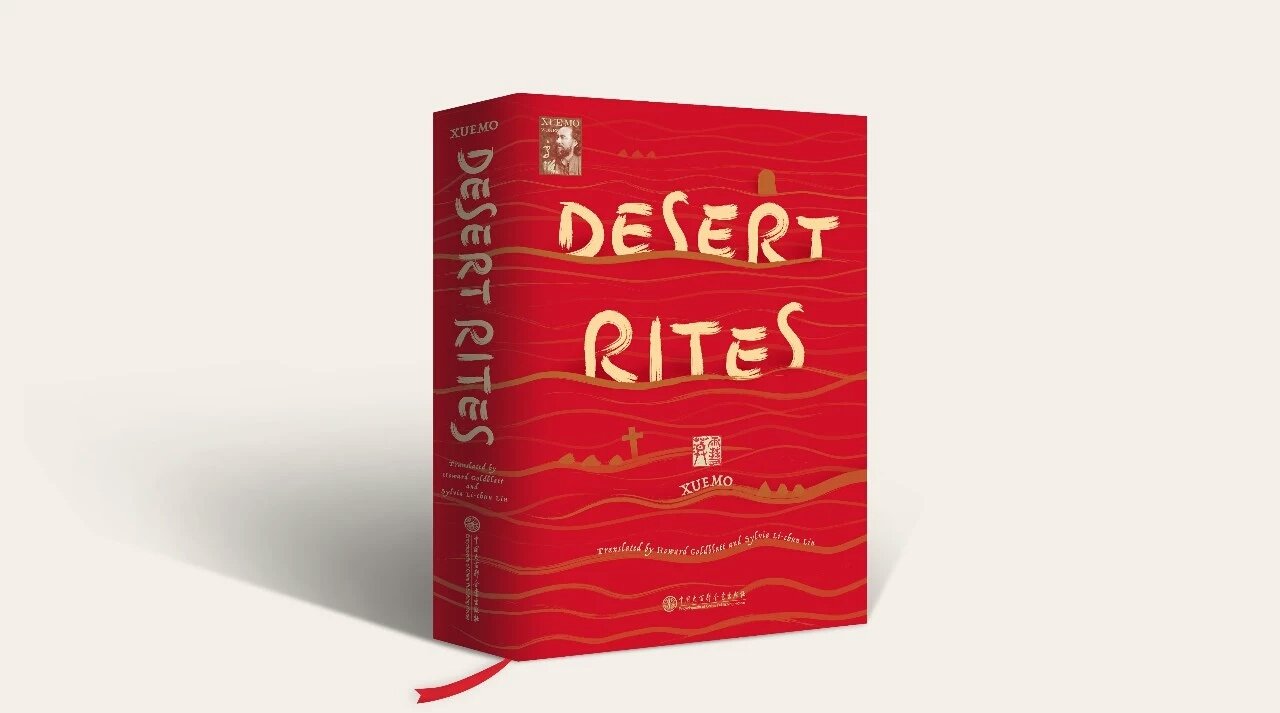

Desert Rites

a novel by Xue Mo

Translated by

Howard Goldblatt and Sylvia Li-chun Lin

Chapter One

1

The rabbit-hawks come in late summer,

around the time of Bailu, or White Dew, when the desert sand yellows, the grass

grows tall, and the rabbits are plump. After a restive summer, they swoop down

from the Qilian Mountains and wheel toward the Tengger Desert in Gansu.

Laoshun set his snare on the dry Dasha

River bed.

Constructed of cotton thread on three

sides, it formed a tripod over a tethered pigeon—the bait. A hawk, famished

from failing to catch any of the increasingly elusive rabbits, flew headlong

into it.

With eyes that can see for miles, it did

not notice the snare right in front of it.

The usual morning task: “crush” a hawk.

Laoshun awoke early that morning, jolted

out of a dream teeming with rabbits that descended on him with bloody mouths,

so many they nearly blotted out the sky. A believer in retribution, he was sure

they were animals that had died at his hands, now coming to claim his life. He

had dreams like that all the time, and after the first time actually decided to

stop flying hawks altogether.

“Nonsense!” Meng Eight had exclaimed.

“Stop and the rabbits will ruin our crops. We’d be lucky if we didn’t starve.”

That comment persuaded Laoshun that

flying hawks was in fact a moral act that accumulated good karma. Mostly,

though, he grew restless and hated the idea of giving up the tasty rabbit meat

after White Dew passed. And yet the killing of sentient beings cast a shadow on

his mind, so the dream haunted his sleep, and he awoke in a cold sweat each

time it visited him. The dream recurred, yet he kept flying his hawks. Rabbits

ruined the crops, and that thought was the “broom” with which he managed to

sweep the shadow off across the mountains.

The moment he turned on the light, the

hawk named “Stubborn Yellow” flapped its wings to show its agitation.

Obviously, it too was having visions, likely dreaming of soaring aloft. That

must be it, Laoshun said to himself. Humans smack their lips when they dream of

eating meat, and a hawk flaps its wings when it dreams of flying. He noticed

that the bird’s eyes were open. Those commanding eyes were always in motion; he

loved eyes like that, true hawk eyes, the windows through which he could see

what made a hawk a hawk.

Stubborn Yellow was an exasperating

bird, hard to care for, with a violent temper; but that meant it was a good

hawk, the way an unbroken horse can travel a thousand li, and a loyal minister

is staunch and upright. The hotter the temper, the more likely that the bird

will turn out to be a treasure. Once tamed, it will be an expert rabbit hunter

and unfailingly dependable. A second-rate hawk like Indigo Widow, on the other

hand, turns docile the moment it is trapped; it eats what it is given and

allows itself to be touched. On the surface, it appears to have been subdued,

but it will fly away the moment it is released. Catch a rabbit? Sniff a

rabbit’s rear end is more likely!

Laoshun preferred spirited hawks.

A thumb-sized ball of wool lay on the

ground. He had forced it down Stubborn Yellow’s craw the night before, and the

bird had expelled it in the morning with a twist of its neck. He picked the

ball up and examined it under the light; it was spotless, which meant that the

bird had cleaned out its phlegm and was now ready to be flown over rabbits.

This was the seventh ball. The previous six had gone in at night and come out

the next morning covered with a viscous yellow substance called “tan,” a term

passed down by Laoshun’s ancestors. Lingguan, his youngest son, said it was

fat. It did not matter to Laoshun what it was called, only that it was the

substance that made a hawk wild. Without removing it, he would lose the bird

the moment he let it go. Swoosh—into the sky and out of sight by the time it

went into its dive. Once the phlegm was cleared, the hawk would experience

vertigo when it flew too high, and hunger would force it to pounce on the first

rabbit it saw.

Laoshun decided that this was the day to

let Yellow Stubborn hunt. Timing was critical. If he held off too long, it

might be too tame to recall that it was a bird of prey. Everything was ready,

and what he needed now was the proverbial east wind. All his training led to

this singular act of setting it loose; Laoshun was as keyed up as a soldier

before battle.

Fresh air greeted him when he opened the

door. It was the cheering smell of a rural morning; his insides were washed

clean with brisk air that filled his lungs and reminded him of cool water. It was

not entirely light out yet, and a few stars twinkled playfully in the sky, like

the shifty eyes of Maodan, the old bachelor of the village.

A deep, drawn-out, and powerful bellow

from Handless Wei’s bull rent the air. It was a huge animal, with a long,

muscular body whose flesh and bones churned when it ran. When it mounted milk

cows, the smaller animals crumpled under its weight. Laoshun laughed, amused by

such thoughts at a moment like this.

Clearing his throat noisily, he knocked

on his sons’ door.

“Time to get up, young masters. The

sun’s high enough to bake your asses. Don’t forget, it’s thanks to your

parents’ gray hair that yours has remained black all these years.”

“All right, enough,” Lingguan grumbled.

“Would your belly burst if you kept your complaints to yourself for a change?”

Laoshun smiled. He knew how to talk to

his sons. If he went easy on them, nothing would happen, like pounding on

water; they would sleep on and ignore him. But they talked back if he came down

too hard, and getting hot under the collar so early in the morning would not

bode well for the rest of the day.

“It’s thanks to your parents’ gray hair

that yours has remained black all these years” sounded just right, stinging a

bit but not too much; besides, it was the truth. Laoshun and his wife had

toiled from dawn to dusk to raise four children, the family’s “young masters,”

sons who don’t act like sons, and sent them all to school. Mengzi had finished

middle school, Lanlan, the girl, had completed one year of middle school, and

Lingguan had gone all the way through high school. Hantou had fared the worst,

with only a primary education. But that was not his fault. A family of six had

depended solely on the labors of Laoshun and his wife until Hantou started work

at the well. On this morning he was not back yet from his night watch.

Laoshun carried a basket of grass into

the animal pen. The familiar smells of animal sweat and manure seemed to bathe

his heart in warm water. This was his favorite daily chore. The black mule,

sired by Handless Wei’s donkey, had grown so fast it was nearly a full-sized

animal at one year. Gimpy Five had his eyes on this mule, pestering Laoshun to

sell it to him. Laoshun could not do that. He might be talked into selling

another animal, but not this one, as close to him as an animal could be. He

could not and would not part with it. Just look at that fine creature, with its

long, slender legs, the essence of nobility. The young mule liked company, so

when it saw Laoshun, it touched his hands with its soft, white lips. That felt

as good as anything he could imagine. Look, here it comes. Patting its neck,

Laoshun scolded tenderly:

“You’re always hungry.”

The mule brayed fawningly, and that made

him smile. The warm spot in his heart stirred anew.

After laying out grass for the mule,

Laoshun heard the camel growl in its shed, a voice that was full and a bit of a

monotone, as if choking back a cry. While it was not as pleasing a sound as the

mule’s soft bray, the camel was his favorite animal. The largest and strongest

of its kind anywhere in the village, it had a fine, smooth coat that was bright

and glistened yellow. Its humps stood tall and straight, like mountain peaks,

in contrast to Baigou’s emaciated camel, with humps like sagging breasts. Its

patchy coat was a sorry sight, matted and covered with straw and twigs, a

camel’s version of a slattern. So sad. It could not compare with Laoshun’s

camel, a voracious eater and a great farm animal that fattened up easily. When

yoked to a plow, it could clear an acre of land with ruler-straight rows in no

time. To be fair, Laoshun favored the camel in part because its molted hair

fetched eight hundred or a thousand each year, providing the family with a

steady income.